|

return to 2003

The

Value of Copywork

by Miles

Mathis

Until about

90 years ago, museum copywork was an integral part of the

education of every young painter. Depending on whether you

were French, Spanish, or American, a sojourn at the Louvre,

Prado, or Metropolitan would have been considered de rigueur.

Those lucky enough to have wealthy parents, patrons, or sponsors

might even have traveled outside the country to find the great

works of the past (Italy was, of course, a favorite

destination). But the advent of Modernism changed all

that. From where we sit, with our simplifying hindsight, it

appears that at the very moment Picasso left his Rose Period, an

historical lifeline that even the Impressionists and

Post-Impressionists respected was cut. The past was no

longer the residence of giants upon whose shoulders we might

stand (to paraphrase Isaac Newton). Instead it became a

dustbin, and our success as artists became measured by how

quickly we could relegate our fathers and teachers into it, and

how long we could stay out of it.

But artistic

indebtedness was not a sin until the present century:

Michelangelo was heavily indebted to the Greeks; Rubens was

greatly influenced by Michelangelo; Van Dyck copied Titian; the

Spaniard Velasquez studied the painters of the Italian

Renassiance, especially Caravaggio, and influenced European

painting from Goya to Manet. The American William Merritt

Chase copied Velasquez in his youth, and John Singer Sargent

copied Velasquez as well as the Dutch painter Frans Hals.

And what would Rodin have been without Michelangelo before him?

In twentieth-century America, the influence of these Old Masters

is still felt, but "art history", so called, has gone

elsewhere. And it is this "elsewhere" that shows

most clearly, I think, that those with the fewests debts also

have the fewest assets.

Now, after

decades of neglect and abuse, classical painting—and copywork

along with it—has seen its ebb-tide and is preparing, one

hopes, for a resurgence. There has been an historical break

that is not easily remedied. But our museums remain a

repository of information and ideas—some them obvious, some

esoteric. In this article I hope to inspire others to

discover for themselves the great wealth that history still

offers those wise enough to seek it. Museums and libraries

have been my classrooms—places where I could research from the

primary source, where I could work mano a mano, literally

hand to hand, with the great artists of the past. Like the

Protestant Reformation, copywork is a return to direct

inspiration, perhaps not divine, but nearly so. One can

remove all intermediaries—teachers, critics, editors, dealers

(the clergy of aesthetics)—and decide for oneself the

importance of Rembrandt or Raphael, Murillo or Zurbaran, Vermeer

or Van Dyck. And by purchasing your education wholesale, as

it were, you will find that you have also saved time: the more

you can control your own progress the more personalized it will

be, and thus the more efficient. You know, for example,

where your strengths and weaknesses lie. You probably have

very specific questions the anwers to which would shore up these

weaknesses, but no one will tell you what you need to know.

Perhaps no one can. The trick is to find someone who

does know and to pry it out of him. The best place to beg

for technical secrets is at the museum, because the artist cannot

say no. You set up your easel, and in the process of

imitation you begin to understand the process of creation.

The information is not told to you; it is intimated, sublimated.

Copywork is truly learning with the right side of the brain, for

the technique is not rationalized but intuited. And since

painting is a capacity of the right-brain, the experience can be

felt directly without the interference of the rational

left-brain. This is important, for the left-brain is an

intermediary just as insidious as the art critic. The great

left-brain—master of technology, statistical wizard, birthplace

of economics, prime-mover of the modern age—and sour scourge of

art. Resist the temptation to overanalyze your work and you

will have taken a giant step toward discovering your Muse.

But before

you discover your Muse, you must first discover your mentors.

By reading widely you can find the artists you most admire.

These artists will teach you to paint: then and only then, if you

are lucky, your Muse will teach you to create.

Once you

have discovered a mentor—an Old Master who inspires you,

say—your first step is to find a book about that artist.

You should look for a recent publication with as many color

photographs as possible. You can buy a book at the

bookstore, of course, or you can do your research at the public

or university library. If you live in a college town, I

highly recommend the fine arts library at the university.

The bookstore will have a few of the newer publications (which

are lovely if you can afford them), but the university library

will have a much larger selection, and you are more likely to get

all your work done in one place. Unless you are also a

student, you won't be able to check anything out, but since you

will just be doing research this won't really matter. Next

to the photographs in the book (or in an index at the back) will

be listed where the original work is located. This is more

likely to be correct and up-to-date in the more recent

publications. Works listed as being in museums are less

likely to have relocated because of a recent sale than works in a

private collection, but always call before you make a long road

trip to copy a particular work. Those works still owned by

individuals may be listed as being in "private collections",

with no specific information included. But some will list

the owner's name. These works are not off-limits to you.

If the owner is nearby, give him or her a call. It may be

possible, depending on the person, to at least view the work.

Many connoisseurs are quite happy to find someone interested in

their collections. If, during the meeting, you develop a

rapport with the owner, you may be able to get permission to

copy. Usually, though, it is much easier to make an

appointment to copy with a museum, which is open everyday, than

to deal with an individual who will have many other demands on

his time. The best thing is to find a beautiful work in a

museum nearby. Reasearching a number of artists at once

will increase your chances of finding an inspirational work.

If you find,

despite your best efforts, that all your mentors' works are in

London or Madrid or St Petersburg, for example, remember that

almost every major city has a museum of fine art. You will

be surprised at what masterpieces many of them have, especially

in storage. In order to discover exactly what these museums

have, it is necessary to find a catalog of the complete

inventory. Again, the library will have many of these.

Or you can send off to the museum for a catalog. You will

probably find that the museum just up the road has a number of

pieces that interest you.

In choosing a work, it is

important to keep in mind what you are trying to learn.

This will vary from trip to trip, but constantly reassessing your

own development will help you choose works that are likely to

answer questions you need answered now. Especially, do not

overreach yourself. It is important that each session be a

positive one. For me, I find it helps to isolate a single

problem and to concentrate on an area in a painting that can be

copied in one day. For instance, with John S. Sargent's

Venetian Beggar Girl (Dallas Museum of Art),

click for detail

I was

interested in the overall looseness of the brushwork. I did

this copy very soon after beginning to use oils and my goal was

to learn to handle a brush the way Sargent did. Therefore,

the small scale of the painting (24 by 18) and its nearly

monochromatic palette allowed me to isolate brushwork as my

exercise. It also allowed me to have a complete painting at

the end of four hours—a painting that I would always have as a

reminder of what I knew and how I knew it.

A couple of

years later I went back to Sargent (Carnation, Lily, Lily,

Rose, Tate Gallery, London)—this time for color.

Again,

I chose an area I could copy at one sitting—in this case about

a quarter of the painting. I was interested in the way

Sargent had worked the little girl into the background, not with

detail, but with bright yet unexaggerated complementary colors,

especially orange and green.

At about the same time, I did

a partial copy of Bouguereau's Admiration (San Antonio

Museum of Art).

Once again,

the canvas is 24 x 18, and I worked for about four hours.

This gave me time to bring the skintones to a fairly high degree

of finish. Since Bouguereau used minimal glazing or

overpainting in his faces, this is all I needed. The trick

to copying a Bougeureau, I discovered, lay more in the choice of

undertone, the absorbency of the canvas, and the choice of white

to use as the base skintone. I had the wrong white, which made

it impossible to match his style no matter what else I did.

Of course,

you may plan an exercise that can't be completed in one sitting,

but I find that many of those who spend weeks and months exactly

copying large detailed works lose the ability to treat the

experience as an exercise. It instead becomes hero

worship—replication rather than the passing of a torch.

This should be avoided at all costs. I might mention,

however, that you should not be afraid of being unoriginal or

derivative while you are learning to paint. All of us who

learned to play chopsticks on the piano as children were not

derivative. We were simply young. You must allow

yourself to go through a learning phase where you are not very

good and not very inventive. Because to become good and

inventive you must first learn to paint. To again use the

musical analogy, if you want to write music you have to learn the

scales. If you want to paint you must first become

technically proficient at applying paint to the canvas.

This is simply a fact.

Once you have

chosen a work to copy, the next step is to contact the museum.

Sometimes you can get all the information you need over the

phone. Unfortunately, just as often you get the run

around. Copywork is rare outside of New York City, Chicago,

and Washington, D.C. (and it is rare in these places, now, too),

and an administrator or curator at a smaller museum may not know

his museum's policy of admission. You may be told that

copywork is not allowed when in fact it is. Don't give up

until you have written a letter to the director stating that you

are a student (you don't have to be enrolled anywhere or look

eighteen) and that you are copying for your own edification (as

opposed to copying for resale). This should get you in.

If you are

interested in copying a work in storage, you will need to get

special permission from the director or curator. An

appointment will have to be made to give the museum time to find

the work and to prepare it for copy. All museums should

have public access to stored works, provided you make an

appointment well in advance. Some will require references.

But, of course, actual policy will vary depending on the museum.

For instance, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, despite being

a first-rate collection, allows no copywork, ever. This is

unfortunate, for it displays not only a large gap in commitment

to public service, but also a forced break in the history of art:

if the young artists of today can't learn from the past, what

will fill the museums of tomorrow? If you encounter other

such instances, I encourage you to complain vociferously.

It is just another example of how our artistic heritage, and the

past in general, is being entombed.

Now, some specific

recommendations:

Always take

an assortment of canvases. You may change your mind about

what to copy once you see the complete collection, or decide to

copy more than one painting. Also, museums rarely let you

copy at the same size as the original: you either have to

copy a detail or blow the full-size canvas up or down by two or

three inches. So build your canvases accordingly.

If you are

copying a work painted before 1900, it helps to have your canvas

already toned (to about the color of raw linen). White

grounds were not used much before the present century. I

have found that the color of the ground is usually not as

important as its value (its darkness). Just throw a

turpentine wash of raw umber or some other mid-tone over your

white canvas. If you paint on a white canvas, it will be

hard to match your values to a painting on a toned ground.

Also, I highly recommend you use white lead as your ground when

copying old works. If you want to match their

effects, you must match their supplies, and I assure you that

none of them were painting on acrylic gesso. If you are

lazy, you can always paint a thin layer of white lead right over

the top of your pre-stretched gesso, and then tone it. This

gives you a quick fix, and provides a ground with less

absorbency. Your brush is then more likely to skate nicely

across your canvas like the old masters.

Always take a

clean cloth tarp to put under your easel. The museums are

not impressed by a dirty tarp, because they have no way of

knowing whether all the paint on it is dry or not. So take

a clean tarp large enough to cover the floor under you and your

easel. That way you can put your paint box on the floor,

and with your palette on your arm the only furniture you need is

your easel.

Invest in a

sturdy collapsible easel. Only the major museums (like the

Metropolitan) furnish an easel. I recommend a sturdy wooden

easel with three collapsible legs. Daniel Smith has a nice

one that is not very heavy for about ninety dollars. It is

much lighter than a "French" easel, and if you are not

a watercolorist you don't need the trays and the horizontal

capability. Obviously, if you are copying a watercolor, you

may want to spend a little more for the French easel. [But

be forewarned that most museums do not allow copying in

watercolors. Water is a greater danger to old paintings

than even oil paint—which can be easily removed with turps.]

It goes without saying that you can also build an easel, but

sometimes the hardware is hard to find. I have never built

a portable easel, but I did build my studio easel, and the

hardware for it could not be had for love or money. I ended

up "borrowing" the hardware from a broken easel that

had been pitched out into the courtyard of the art building at

the university. As artists we must be creative in so many

ways.

Take a paper

bag or a piece of cloth to wrap your used brushes in. You

don't want to have to clean all your brushes at the museum.

Take a small

box of pastels and conte crayons. If the museum absolutely

refuses to give you permission to paint, you can almost always

draw instead. For some exercises this is just as good.

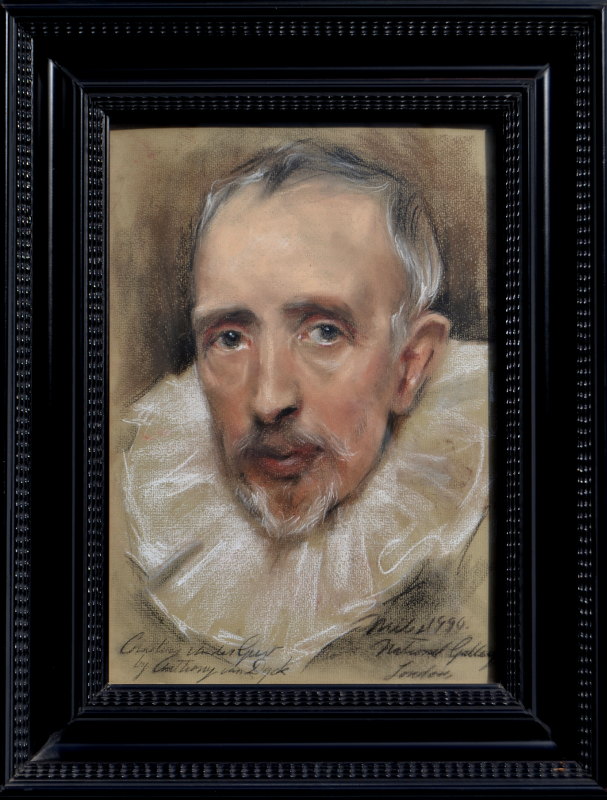

When I copied Sir Anthony Van Dyck's Corneliis van der Geest

(National Gallery, London) I couldn't get permission to copy in

oils on the same day.

I was in a hurry, so I did a drawing instead. Since

I was interested in how Van Dyck had captured the old man's

character through lighting, detail, and color, pastels worked

very well.

Finally,

don't forget the importance of drawings. Drawing is not

only the basis of painting, it is also an exercise worth doing

for its own sake, or for the sake of beauty. And unlike

paintings, drawings can be copied with a great deal of success

from photographs in books (especially charcoal and pencil

drawings). Line quality can be copied and learned both for

its own sake and as it relates to brushwork. Developing

expressive line quality will help you develop expressive

brushwork. In copying drawings, choice of paper is very

important. You must match the texture very closely in order

to match the line quality. In this the only tools you have

are intuition and trial and error. I matched the effect of

Peter Paul Rubens drawing Daniel in the Lion's Den

(National Gallery, Washington, D.C.) with a sheet of

Japanese Kitakata that I first dusted with charcoal and rubbed

heavily to effectively "antique" it. Then a piece

of willow charcoal, fairly well sharpened, gave me the line

quality I wanted.

Copying teaches you the importance of the surface and

tools in creating an effect, whether with charcoal or paint.

Matching brushwork is more than just loosening or tightening your

wrist, for example. In copying an artist like Sargent you

must have fairly oily paint and a very smooth, non-absorbent

canvas. Whereas if you wanted to copy the great Russian

painter Nicolai Fechin, you would have to blot all the oil out of

the paint and use a canvas with more tooth. You would also

have to give up your filbert for a bright and a painting knife.

Learning these technical aspects can save you much frustration.

Many students blame themselves for lack of skill where the only

problem is incompatible paints, brushes, canvases, and desires.

Remember,

too, that technique is just a tool. Once you have mastered

technique, then you must teach yourself to create. This you

can learn from no one. The ultimate goal is to justify your

technique by putting it in the service of your ideas, and to

attain a level where these ideas have a quality all their own.

In the end, what one learns from the masters that is most

important is that great artists are not just virtuosos or

brilliant technicians. Nor, as we have had ample evidence

in the 20th century, are they simply groundbreakers, visionaries,

or ideamen. History teaches us that they must be both:

masters of an expressive medium with ideas of a depth and

sophistication worthy of expression.

If this paper was useful to you in

any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE

THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing

these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by

paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de

plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might

be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33

cents for each transaction. If the link below is broken, donate

through the kitty on my front page or updates page.

|