![]()

Email

webmaster at mm@milesmathis.com

click

here to

read disclaimer

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

translated

by

Liam

Tesshim

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

![]()

![]() Preface

Preface![]()

It

has been the assumption by many of those in the world of letters

that Professor Tolkien's discovery of The

Red Book of Westmarch (and other

writings) in the early 20th century was not so much an exhumation

as a fabrication. That is, like James Macpherson and the famous

controversy of Ossian two hundred years earlier, Mr. Tolkien was

considered not an historian but a fiction writer. But unlike

Ossian, the existence of Mr. Tolkien's sources was never even

questioned: they were dismissed by all but the most credulous (or

faithful) readers out of hand. The documents were believed to be a

literary device; almost no one took them seriously. This saved

Professor Tolkien the trouble of proving his assertions, but it

has led to serious misunderstanding.

It is surprising that no one found it at all strange that a

professor of philology with no previous fiction writing

credentials, at a premier university, should be the one to

'imagine' an entire history, complete with vast chronologies and

languages and pre-languages and etymologies and full-blown

mythologies. No one thought to ask the question that was begged by

all this: if a previously unknown cache of historical documents of

a literary nature were

to surface anywhere on earth, where would

that be? At the top of the list would certainly be the archaeology

departments of Oxford or Cambridge. Who else is still digging in

the British Isles? Who else cares about such arcane (and

provincial, not to say insular) matters? And who would these

archaeologists consult when faced with unknown languages in

unknown characters in untranslatable books? They would go first to

their own philologists in their own universities, to experts on

old northern languages. This is exactly what Mr. Tolkien was.

Coincidence? I think not. And when those discoveries were found to

be of the nature they were—positing the existence of hobbits and

elves and dwarves and dragons—is it any wonder the

archaeologists washed their hands of the whole mess, never wishing

to jeopardize their careers by making any statement about the

authenticity, or even the existence, of their great find? One

would expect them

to make a gift of it all to the eccentric philologist who believed

in it, though it was not in the least believable. To let him hang

himself out to dry in any way he saw fit. Who could have foreseen,

after all, that he would publish it to ever greater wealth and

fame, and never have to explain a thing? The strange turns that

history takes, not even the historians can predict.

The truth is that The Red Book

(or a copy of it) did, and probably still

does, exist. Nor is it the only surviving document, or trove of

documents, from that part of our history. Other sources have

recently been unearthed, in related but separate locations, that

confirm this. It is true that the ruins of Westmarch were long

thought to be the only existing repository of hobbitlore and the

history of the elves. And it is also true that the present-day

location of what was then Westmarch is still under a cloud. Only

Professor Tolkien, and perhaps one or two from the archaeology

department at Oxford, ever knew its exact locus. But, as I said,

other fortuitous digs have yielded new evidence that Westmarch was

a real place, and that The Red

Book was an historical fact.

It is known to all of the wise

(in hobbitlore) that Westmarch was only one of many population

centers in the Northwest of Middle Earth. Bree, Buckland,

Hobbiton/Bywater, Tuckborough, and several others in fact predated

the settlement at Westmarch, and were not eclipsed by it until

later in the Fourth Age. What is not as well known, because it was

not included in The Red Book

or accompanying artifacts, is that other

settlements to the north and south of the Shire also gained

pre-eminence later, and were therefore the natural repositories

for important documentation. The wealth of material since

discovered in these other sites not only rounds out our

understanding of the Third Age, it often fills in gaps in the

first two ages. And, most importantly, it supplies us with

completely new information about the Fourth Age. The present

volume is proof of that.

The tale told here is taken from

The Farbanks Folios,

an anonymous compilation of oral histories and Elvish lays

probably composed sometime in the Fifth Age. None of the tales in

these folios has been given a title in Westron (such as 'There and

Back Again'), since none of the tales herein appear to have been

written by any of their protagonists. There is no first person

narrative, and much of the detail can only have been supplied by

an 'omniscient' third-person writer living at a great distance in

time from the action of the story. In that sense these are

secondary sources, just as the all the information about the Elder

days in The Red Book—that

is, 'Translations from the Elvish'—is also (but as 'There and

Back Again' is not—if it was in fact written by Bilbo.)

The Farbanks Folios as

a whole deal with any number of events and narratives, as well as

poems and songs. The present selection from them concerns only one

major event, told in a single narrative. Although the author is

unknown, he (or she) is assumed to be a hobbit. The other contents

of the folios, and their similarities and linguistic connections

to the Westmarch documents, makes this supposition unavoidable.

The author has incorporated bits and pieces from other sources,

such as from the elvish and dwarvish oral and written histories of

the day. These external sources are occasionally the subject of

other narratives among The

Farbanks Folios, and in these

cases I have taken the liberty of including pertinent information

in the present tale, either by simply putting it in the tale

itself (with a footnote), or adding it as a footnote. I have done

this only when I considered it of utmost importance. Publication

of overlapping tales, many of them incomplete, presents

difficulties which perhaps cannot be solved to the satisfaction of

everyone. All I can do is indicate my actions, and the reasons for

them. It is hoped that the audience may remain indulgent, as long

as their patience may be ultimately rewarded.

Liam Tesshim

Swansea, Wales

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Book

1

News

from

the West![]()

![]() Chapter

1

Chapter

1![]()

A

Visitor in Brown

Primrose

Burdoc adjusted the skirts of her pale-blue dirndl and patted her

curly hair back into place as she approached the bridge. Over the

water she could see the round doors and windows of Farbanks and

the row of tidy gardens along Willow Way. But mostly she could

see—because she was looking that way all along—a hobbit in a

dirty yellow overall and an old straw hat kneeling amongst his

potatoes, up to his knees and elbows in mud. If she hadn't known

him immediately, he certainly wouldn't have been of any interest

to her—a hobbit lass of 24 summers and as picky as any.

In his present position, he was not likely to impress any passing

female, not if she were 8 or 80. But Primrose, or Prim as she was

called, knew the hole and the garden—yea, she knew the very

straw hat on his head and loved it, though it was ever so

unlovely.

The time of the year was mid-autumn and though

the season had so far been mild, the nights were chilly. As the

sun began to set Prim increased her step and pulled her shawl

about her shoulders. But at number 8 Marly Row she stopped and put

her basket of berries on the ground. Then she crossed her

arms.

'Mister Fairbairn!' she

said to the muddy posterior and undersoles of the grubbing hobbit.

'If you haven't noticed, it's almost dark.'

The hobbit turned round and squinted at her from under the

crackled brim of the hat. 'Oh, yes—Prim, is it? Thank you, yes,

it is late. Thank you.' And he turned back around and continued to

muck.

'Tomilo* Fairbairn!' she

continued to his backside, as if she were used to addressing that

position. 'Do you propose to go on lying in that cold mud until

your hands freeze up and the frost sets on your toes? I should

just like to know, so that I can tell the mourners when they

ask.'

Tomilo turned and squinted

at her again, with perhaps a slight twinkle in his eye. Perhaps

not. It was hard to tell in that light. 'Hm, yes, the mud is a bit

cold. Thank you. I'm almost finished. I hope your mother is well?'

And he returned to the mud.

*His

name was Tomillimir, but everyone in Farbanks shortened it to

Tomilo. The Fairbairns were descendants of Samwise the Great,

through his daughter Elanor Goldenhair. Moving to the Westmarch in

1455 (Shire Reckoning), the Fairbairns naturally became interested

in Elvenlore and language. Tomillimir is a name of Sindarin

origin, meaning 'jewel of the sands'. The elves had intended

'tomillos' to mean the sands of the seashore, but the hobbits took

it to mean sand more generally, including the sand removed from a

burrow.

With a slight humpfh Prim adjusted her

shawl, picked up her basket and returned to the lane. She looked

back once, but as Tomilo was not watching her, she humpfhed

lightly again and walked on.

About a quarter of an hour

later, as the sun finally dipped all the way behind the hill and

it was just beginning to get really dark, Tomilo looked up again.

He looked first at the road. Then he looked at his hobbit hole and

the dark round windows, shuttered with green half moons on wooden

hinges. The white curtains, looking blue in the moony light,

shivered in the evening breeze. Suddenly Tomilo felt cold and he

got up and washed his hands and feet in a pail of rainwater under

the eaves. Then he went inside and lit the candles and the fire.

In the kitchen he lit another fire and started his toast and tea.

As he put on his housecoat the kettle began to sing. In a moment

he was at the fireside, his feet roasting on the fender, and his

plate high with toast and honey and butter.

After supper he took down the candle and began to search for his

pipe. Now, it should be in his morning housecoat pocket. Barring

that, it must be at the bedside table. No, of course, he had left

it on the lawn chair. But as he rummaged in the dark, even feeling

about in the grass in case it had fallen, he thought he remembered

putting the pipe in the right-hand pocket of his green breeches.

Before he could run into the hole to test this latest theory,

though, a thing happened. Not a great thing, mind you. But

maybe one of those things that somehow leads to a great thing.

That is how he thought of it later, anyway.

For he heard the clop of a horse's hoof, and the next thing he

knew a black figure emerged out of the lane and came toward him.

Suddenly a lantern was uncovered and the figure said, 'Tomilo, is

that you?'

'Of course it is me;

this is my hole isn't it? Who else would be standing outside my

hole searching for my pipe? Is that you, Bob Blackfoot?'

'Of course it is. Who else would be wandering about Farbanks after

sundown with a wizard on his heels.'

'Beg pardon?'

'I mean who else

but the acting mayor is qualified to make these decisions?'

'Beg pardon? Bob, have you got someone there with you?'

'Yes, Tomilo, that is the long and short of it. Invite us in and I

will introduce you.'

Tomilo did

invite them in, and when he had re-entered the parlour and lit

another candle, he turned round to see who his other guest was.

What he saw surprised him, even though he had had some warning.

Bob had indeed mentioned a wizard, but Tomilo had assumed it was

all part of some jest. Standing there in the middle of the room,

bowing his head to keep his tall hat from crushing its point on

the low ceiling, was an old man with a white beard and a staff.

His black kneeboots were heavily weathered and caked with grey

dirt. His cloak was a rich brown, with a fur collar. On his

forearm he wore a strange leathern device that Tomilo did not

recognize. About his neck hung a heavy gold chain bearing a single

precious stone with a warm brown glint. It flashed now in the

candlelight and then went dark.

'Tomillimir Fairbairn, at your service,' said the hobbit finally,

with a bow.

'Radagast the Brown

at yours,' returned the wizard. 'Perhaps you have heard of

me?'

'Sorry, no,' answered

Tomilo.

'Hm. I should have

guessed as much. But you are a hobbit, so perhaps you have

heard of Gandalf. Had some connections to Hobbiton, almost two,

no, what is it, three hundred years ago now?'

'Yes, I have heard of him. I read about him in The Red Book

once.'

'Yes, that's right. Now

wait a minute,' said Radagast suddenly. 'Fairbairn. You aren't one

of the Tower Fairbairns are you, the Wardens of the Westmarch?'

'My family comes from there,

yes. I am not one of the Fairbairns. But I am a

Fairbairn. One of my cousins is a warden. I have never met

him.'

'There are a lot of

Fairbairns now, I suppose. Just like Took or Brandybuck or

Gardner. They're all over. Not room in the Shire for all of them,

I guess. I suppose that's why you're here?'

'In a word, yes. There are other reasons, but that will do for

now. But what about Gandalf?'

'Oh, Gandalf. Gandalf was a wizard, you know. One of five. I am

one of the other four, you see. He was Gandalf the Grey. Or

Gandalf the White, I should say. At the end. Or after Saruman the

White was removed from the order. I am Radagast the Brown.

That is my colour. There are other wizards, other colours. But

that is neither here nor there. It may soon be, actually,

but it isn't now.'

'Yes,'

offered Tomilo expectantly, waiting for Radagast to state his

purpose.

'I am a wizard,'

repeated Radagast.

'Yes,'

repeated Tomilo, looking to Bob for help.

Bob jumped to Radagast's side. 'Mr. Radagast here needs a message

took to the Moria. None of us could do it; we're all that busy,

you know. Besides, our families wouldn't allow it. The wives and

all. So Mr. Radagast here suggested a bacheldore. Someone who

could go to the Moria with a message and not be missed. I mean not

be missed overmuch by his family, if you see what I mean,

Tomilo.'

'Yes, Bob, not to

worry, no offense taken, none meant neither I guess. But to Moria,

you say? Dwarvish message, is it? They should run their own

errands, the dwarves; then a hobbit, or even a wizard, Mr.

Radagast is it?, could be left to his own taters.'

'It's not a dwarvish message,' answered the wizard. 'It's a

message to the dwarves. And to others. I have many such

messages to be taken all over: north, south, east and west. More

than that I cannot tell you. Except that the message is very

important. If someone from this village does not deliver it, I

shall have to go myself. But I am expected in Gondor, to take the

same message to the King; and also to Edoras. If you could see to

leaving your garden for a fortnight, Mr. Fairbairn, I am sure Bob

here could have someone keep an eye on it. And I can supply you

with a pony. Working with beasts is a specialty of mine, you might

say.'

'Well, I suppose I could

get away for a week or two, if you can scare up a pony from

somewheres. I'd rather not walk all the way there, it getting

along in the year as it is—and I do have work to do, family or

no.'

'Good, then it's settled,'

said Radagast, ignoring this last part. 'We'll leave first thing

in the morning. I can ride with you as far as the Greenway—I

mean the New South Road, of course. After that you will be on your

own. Now I must go out and see to getting the pony here in

time.'

'Tomorrow morning! Sakes!

Good gracious me! If we're going to rush off, why not go now? I

can leave without any pocket handkerchiefs or warm clothes and be

miserable the whole way. And get chased by dragons and swallowed

by trolls and who knows what else. I've barely finished my supper

and now I'm expected to pack. Why, I don't even know where my pipe

is. Who can be expected to ride to Moria without a pipe?'

'Be calm, my good hobbit,' said Radagast, smiling to himself. He

understood Tomilo's meaning well enough: The Red Book was

well-known not only among hobbits, but now among the wider world

as well. 'Nothing to get bebothered about,' he continued.

'We'll leave in the morning when you are ready. Take your time,

but don't pack too much. The pony is long-legged and spry, but he

won't like a heavy load, even with half of it a halfling! Do try

to get up early, though. Be prepared, but don't dawdle. Oh, and

your pipe—it's on the mantel behind you.' And with that he swept

from the room and leapt on his horse, clopping away into the

darkness.

'Well, he's a caution

and no mistake,' said Bob, as the sound of hooves died in the

distance. 'He came riding in about an hour ago from the west, as

if all the sons of Smaug was on his tail. Strolled right into

meeting and asked for the mayor. Never even took off his hat.

Mayor Roundhead is in Sandy Hall, of course, for the Quarters, so

I had to do the honours. You know the rest.'

'What's this message? Does it sound important?'

'Don't know. It's writ down and sealed, he says. You're not so

much delivering a message as carrying a letter—that's what I

would say, Tomilo. I wonder if it's that he don't trust hobbits?

Just to remember it, I mean. And not to tell no one else.'

'Unlikely. Probably just a letter that don't concern us. Although

if it's the same as one going to Gondor—and everywhere else, as

he says—it should concern us, too. We've probably just been left

out of reckoning again.'

'I

don't know. If it means we'll be left alone, I say all to the

good. I'd just as soon be forgot and stay forgot, as far as news

goes anyway. Anything that concerns hobbits, we'll hear about it

from the Shire. You take care, now. We'd appreciate a report when

you return, if you think about it. Oh, and don't dawdle,' he added

with a chuckle and a handshake.

Tomilo sat by the fire,

thinking about tomorrow. And yesterday. First of all, he decided

not to bother with packing until the morning. It was too dark to

go looking for everything with just a candle. And he would take

his time in the morning, too. If Radagast left without him, he

left without him. As long as the pony was good, he could make it

to Moria on his own. He knew where Moria was. Due east. He'd never

been there, but he knew well enough.

Since the fall of Sauron and the end of the Third Age, times had

been peaceful and easy. No one thought of goblins or wolves, much

less dragons or black riders. Tomilo knew of them, it is true. He

had read about them in the books in the museums—in Undertowers

or Great Smials. But they were all creatures of the past, the last

ones killed by his father's fathers' fathers, he thought. A trip

to Moria was simply a good excuse to get out of Farbanks for a

spell; to be on the road again, out under the stars. Farbanks was

becoming just like the Shire. He had felt like the last bachelor

in the Shire, and now he was the last bachelor in Farbanks. Or the

last bachelor over thirty-five. It was rare now for a hobbit male

to get out of his tweens untaken. Families were large, and the

sooner they started, the larger they could get. This was fine with

Tomilo. He came from a large family, of course, and he liked

company. But he had never been one to rush into things. At

thirty-six, there seemed more reasons for not marrying (yet) than

for marrying. That was all. There were things to do first. What

things, he was less and less sure. Still, something told him to

wait.

So here he was in

Farbanks, almost a hundred miles south of the Three Farthing Stone

and more than fifty miles from the Old Forest. The last hobbit

settlement in Eriador. The Town Hall itself, the only building in

the village, only went up forty years ago. But it was needed, all

said. Farbanks was needed for overflow, if nothing else. And then

there was the trade with Minhiriath; and of course the leaf grew

so well down here.

There were

already bustling communities in the Tower Hills (where he had come

from), the South Downs, even Fornost. Arthedain, that the hobbits

called the North Farthing, was the most populous place west of

Bree. Oatbarton alone was now bigger than Hobbiton and Bywater put

together!

When Tomilo had moved

from the Tower (as it was called), he had hoped to find things

different on the frontier. He had envisioned a bit of excitement.

New faces, new folks. Work to be done. But hobbits are a

proficient race, and most do not hearken to excitement. Within the

first few years Farbanks became as domesticated as Took Hall,

everything running in its groove, well oiled and pleasant. In fact

it was better, from the hobbit point of view, than Took Hall; for

Took Hall had its eccentricities still, and its strong characters.

Farbanks had no use for such things. There were no weeds in the

gardens, no dead leaves on the thatch, no stones in the road. The

mill ground its grist and the maidens sang and the children played

under the Great Mallorn.

Tomilo

fell asleep with the front door and all the windows open,

satisfied with this bliss and yet somehow uneasy. He had no fear

of burglars, but his dreams were fitful nonetheless.

The

morning dawned clear and chill. As soon as the first ray stole

through the front window and creapt across Tomilo's bed, he was

out of the covers and collecting his gear. His packs were on the

lawn, checked and re-checked many times before Radagast appeared.

The sun had just begun to warm the dew when that wizard rode up on

a well-formed bay with untrimmed mane and tail. Behind him trotted

a slender mottled-grey pony—quite tall for a pony and a bit

intimidating to Tomilo.

'Sorry

I'm late,' announced Radagast, with no other greeting. 'I sent

word to Bombadil last night, but the birds took their time.

Drabdrab just arrived, and he's already tired and sleepy. We'll go

slow and make it a short day. Still, we should get to Sarn Ford

before we rest.'

Drabdrab was

equipped with a saddle of superior workmanship, long worn but

finely tooled. It had strange shapes cut into its flaps and

intricate patterns even on the girth and stirrup leathers. It was

also equipped with breastplate and breeching, but these were thin

and mostly ornamental—for the hanging of bells or other

decoration. Tomilo knew somewhat of working leather, and he asked

Radagast about the figures and the tracery.

'That saddle was made for an elf child, I believe. Where or by

whom I don't know. Imladris or the Havens, I would guess. Or

Iarwain—that is, Bombadil, I should say—may have kept a much

older saddle, from Eregion I suppose. Leather generally wouldn't

last that long, but Bombadil has his ways. Those are tengwar,

or elf letters, as you would call them, those lines running along

the edge. Certar, or elf runes, are usually used for

incising, but leather allows for the curving lines, so that the

craftsman has preferred them here. I would read them for you, but

they are too small for me to see without dismounting, and we are

already late as it is. Remind me and I will translate them later.

The larger lines are probably just decoration. Hop up and I'll

tell you more on the road.'

Tomilo slung his packs behind

the saddle and cinched them on. Then he scrambled uneasily up

behind Drabdrab's neck. His legs were too short, and he had to

climb back down and adjust the stirrups. Even at their shortest

they still hung below his feet. Once in the saddle, his balance

was good, so he just had to let his feet hang, unshod and

unstirruped. 'Hobbitback', he thought.

Radagast headed down

the Farbanks' road, southeast, and Tomilo followed. He gave

Drabdrab no signals with the reins: it was unnecessary. The road

was straight, Radagast was ahead on Pelling (the big bay horse)

and what else was there to do but follow. As they got to the edge

of town, though, Tomilo heard someone calling to him and he pulled

Drabdrab up. Radagast stopped also. The Burdoc hole was the last

in the bank to the north of the road, and Primrose was at the gate

looking toward Tomilo. Suddenly she ran up to Drabdrab and patted

his nose.

'Where are you going,

Mr. Fairbairn? You look packed for a while.'

'I'm just delivering a letter to Moria, Prim. I'll be back

soon.'

'Are you working for the

post now?' she asked with a smile.

'No. Bob asked me to do this special. It's important or I

wouldn't. I'll be back.'

'All

right. Don't burgle any dragonhoards. And if you do, bring me back

something pretty. You take care of him Radagast!' The wizard

tipped his hat to her, and they trotted the horses back into the

lane.

'Who was that?' said

Radagast. 'Fiancee?'

'What do

mean "Who was that?" She knew you. How did she

know your name?'

'Oh, I've seen

the lass a time or two, gathering berries. I ride in this area

occasionally, looking for lost things, finding found things. She

has a bright eye, doesn't she?'

'I suppose,' answered Tomilo, grumbling.

After a couple of

hours the two riders came to the main road from the Shire to Sarn

Ford. A turn to the northwest would have taken them to Waymoot,

and beyond to Little Delving. But their way was south and then

east. Not a soul was to be seen for miles in either direction. The

traffic of Eriador stopped for the most part at Farbanks. Men did

not use this road, and the occasional elf or dwarf who did were

rarely to be caught doing it.

All that day Tomilo followed Radagast, speaking little. For a

hobbit Tomilo was rather taciturn, having lived by himself for

many years, and so having lost the habit of easy speech. As for

Radagast, he was the least social of all the wizards, and wizards

are a rather solitary lot to begin with. Whilst Gandalf had

wandered about all the Western World, having his hand in the

affairs of almost every region, and most households; and whereas

Saruman had at first attempted to befriend the elves—especially

the Lady Galadriel and Lord Celeborn of Lothlorien—but had in

the end to make due with the company of orcs; at the same time

Radagast had always lived alone, either at Rhosgobel or in his

solitary rides through Mirkwood and Wilderland. Radagast's only

friends had been the beasts and birds, with whom speech was partly

or wholly unnecessary. So it was drawing on toward evening before

Tomilo finally thought to ask a question.

'Mr. Radagast, Sir, I were wondering if we might stop for a bit? I

do believe Drabdrab is almost done up. What with not sleeping at

all last night, as you said.'

'So he is, my boy. I almost forgot, with all this on my mind about

Moria and Gondor and everything else. I'm usually quite aware of

the beasts and their needs—I suppose I'm not really myself these

days. We'll stop just before we reach Sarn Ford—over the next

rise and down the slope. Of course, it's not a ford anymore, not

since the King built the bridge, but that's what they still call

it.

Radagast and Tomilo had so

far travelled quickly. The wizard had not wanted to press

Drabdrab, but the horses had been trotting or galloping much of

the way. Only on uphill stretches, or when the road turned bad,

did Radagast allow the beasts to walk. So they had made it to the

vicinity of the bridge by nightfall.

Tomilo had been over the Baranduin only a single time—on a

daytrip to Bree long ago. But the great river was much larger

here, only some 50 leagues south of the Brandywine Bridge, having

gained the flow of the Withywindle as well as several other

smaller rivers. It was still muddy and red, and Tomilo thought to

himself that he would not want to fall into it. The water looked

very cold. He and Radagast did not cross yet, but made camp to the

right of the road, under a small copse of trees, in clear view.

They were not hiding from anyone, nor did they fear to meet

travellers. In fact, Radagast quite hoped to meet travellers,

especially dwarves. He could not pass on important messages to

those met on the road, but he could learn somewhat from them about

the news on ahead, on the road or off it. And the affairs of the

various peoples had suddenly taken on a new urgency for him. To do

what was necessary over the next several months, Radagast must

learn everything possible about all those around him—their

trusts and mistrusts, new alliances and long-standing

grudges.

It was in the recent

memory of Radagast that none would think of stopping near a

crossroads or a ford such as this great bridge. In these newly

prosperous times, however, such spots were the best place for

travellers to congregate, to camp after nightfall, and to expect

visitors with tales of new wealth, new discovery, and larger

families and towns. If this is what Radagast desired, he was not

disappointed. He and Tomilo had arrived early, but soon after dark

a travelling band of dwarves came over the bridge and made

directly for Radagast and Tomilo's blazing fire. The hobbit could

hear them singing as they tramped along: a proper dwarf song of

gold and silver and hidden hoards of wealth.

In a deep

dark cave in the mountain's lap

We delve straight down with a

mighty rap

of our pick, ho!

Then we take what we finds

from

the glittering mines

as long as it shines

out bright, ho!

And none can blast the great black stone

or chip and crack

the earth's backbone

like Durin's kin!

Not elves or men!

Not

by the beard on Durin's chin!

Be it silver or gleaming gold

or

clear-white jewel or metal cold

we will find it

earth can't

bind it

from the tools of dwarves, ho!

The song ended

as they came into the firelight—clumping loudly in the dark as

only dwarves can—and bowed low, introducing themselves in turn.

'Frain, at your service.'

'Bral, at your service.'

'Kral,

at your service.'

'Min, at your

service.'

'Radagast the Brown,

at yours and your entire family's, I'm sure,' replied the wizard,

not bowing, but only touching his brown stone with his right hand

and peering again into the fire. 'Oh, and this is my travelling

companion, the estimable hobbit, Tomillimir Fairbairn, of

Farbanks.'

Tomilo bowed low, but

looked at the dwarves uneasily. Although a wide traveller among

hobbits, Tomilo had not met any of the Naugrim before, and he

found their hard-edged visages and abrupt manner disconcerting.

Their clothes, too, were exceeding strange: dark and loose-fitting

kirtles, heavier surely than the weather called for. And with

boots large and wide enough for a very large man. Even Radagast's

boots were not so large. He might have worn Frain's boots as

overshoes, with his own boots inside.

'Do you come from Khazad-dum, as I suppose?' asked Radagast. 'And

is all the news still good from there, I hope?'

'The answer to both your questions is yes and yes,' replied Frain.

'The news is good. So good, in fact, that we would have little

reason to return to our mines in the Blue Mountains but for family

that has remained there. My brother, Kim, prefers our place there.

Less competition for space, and for reknown. It is still true as

it always was that for mithril, there is no place to compare to

the mines of Khazad-dum. But for jewels, the Ered Luin still

yields great wealth.'

'That is

true,' added Kral. 'In fact, with new tools made of mithril, we

are delving deeper and discovering more than ever before. All our

mines all over Middle Earth are yielding more, due to the use of

mithril tools, as well as the abundance of dwarves to wield them.

Now that we are not constantly at war, we may work doing what

dwarves were made to do.'

'Mr.

Fairbairn is travelling to Moria,' interrupted Radagast. 'I hope

the roads remain in good repair.'

'They do. But I wonder why a hobbit is going to Moria?' answered

Frain. 'We have had no trade with the Shire, save for pipeweed, in

many years. Might I ask if you are a trader in leaf, Mr.

Fairbairn?'

'No. I have a

message from Cirdan for King Mithi.'

'From Cirdan of the Havens? Is it important?'

'I do not know. I am only the messenger.' Tomilo left it to

Radagast to explain, if he would. But Radagast changed the

subject. It was clear he felt the message to be appropriate for

King Mithi, but perhaps not for idle conversation with every

passing dwarf, no matter how trusty they might at first appear.

'Do you know anything of the

Great South Road?' asked Radagast. 'I myself am travelling that

way and wonder if there is any news from Rohan or the Gap. Is

Orthanc still deserted?'

'For

all we know Orthanc is as it was five years ago and fifty years

ago—naught but a haunted tower,' said Bral. 'It is rumoured that

the treemen kill any who come near. Dwarves have never had any

love for forests, or for the creatures in them, so we do not go

that way or speak of it. When we travel to the Glittering Caves we

cross far down the Isen and come in from the west, hugging the

foothills of the Ered Nimrais. As for the South Road, there is no

news. But the folk of Dunland are not ones to make news or pass it

on, and we ask no more. I think you will find everything remains

quiet. But if you are Radagast the wandering wizard, as I think,

you will know as much as we do about the ways over and around the

Misty Mountains.'

'I am

that Radagast, as there is no other, but I have been in Eriador on

one errand and another since the first of the year. The eagles and

lesser birds of Rhovanion do not often travel west of the

mountains, and I have been left without my usual sources of

information. I must arrive in Minas Tirith—I mean Minas

Mallor*—before the end of the month, so I must gather news on

the hoof, as it were. There is really no time to lose.'

'Sarn Ford to Minas Mallor in a fortnight? You will have need of

your friends the eagles if you desire such speed. Your mount will

be halt before you reach Edoras, though I would not let such a

beast carry me even across the river. Your feet will carry you

there more surely, though perhaps with less haste.'

'I plan to change horses in Rohan. Good Pelling here is from the

West Emnet in the fields of the Rohirrim, and he will carry me

there as surely as any, and need no prodding as we get closer to

the grasses of his home. But perhaps you can at least tell me of

the Dwarvish settlements in the Green Mountains.* Does trade

remain good between Minas Mallor and Krath-zabar?'

'It is good. We still do not mine north of Nurn. And we have yet

to explore the Ash Mountains. The fear of Barad-dur and Minas

Morgul remains strong and overcomes even our love of delving and

our need for untapped veins of ore. It is said that Sauron sapped

all the strength from the mountains about Mordor long ago, to feed

his fires and his armies, and so we have an excuse for staying

away. But in the Green Mountains, that once were the Mountains of

Shadow, we have not found this to be so, at least south of

Osgiliath where we have dared to go. The range there is mostly

untouched, since Sauron oversaw almost no work—he only stole

from the hoards of others. It is said that the dwarves of Khand

supplied him with iron for his armouries; but where it was mined,

we know

*The

name of Minas Tirith had been changed by King Eldarion to Minas

Mallor: 'tower of the rising sun.' And upon the rebuilding of

Minas Ithil, it was also renamed: Minas Annithel, 'tower of the

setting moon.' Two reasons were given for switching the

nomenclature (remember that it had been 'tower of the setting

sun' and 'tower of the rising

moon'). The first reason given by Eldarion was that

the sun could be seen to rise in the east. Minas Mallor faced

east, hence the logic of the name. His Steward complained that the

Ephel Duath blocked any view of the rising sun. But the King

replied that, by that way of thinking, the name Minas Anor had

been just as senseless, since Mt. Mindolluin blocked the sunset.

The second reason given by the King was that the moon had always

been a metaphor for the elves. The age of the elves was waning,

the age of men was waxing. Therefore, after the fall of Sauron,

the name Annithel was more descriptive. The Steward agreed on this

point. And at his urging, the Ephel Duath was also renamed: Ered

Galen, the Green Mountains.

not. We still do not

communicate with the dwarves of the east, who fought for Sauron,

or at least were under his dominion. Most have fled into the far

reaches of Rhun and beyond, where our knowledge ceases.'

'You have a king now at Krath-zabar?'

'Yes. King Rath. The High King remains at Erebor. But we also have

kings at Moria and the Glittering Caves. They are independent but

remain under oath. Little allegiance is required in times of

peace, but we retain our all our traditions. Our kingdoms are very

strong.'

'Good,' said Radagast.

'That is as it should be, my good Krain. The dwarves are a wise

people in their way, and we need your strength. I am glad that you

prosper. Now, I was wondering, can you be so good as to tell Mr.

Fairbairn here the proper ways to approach your gates at Moria? I

have not knocked on your door, so to speak, from the west—I

always pay my visits, rare though they are, from the east,

arriving from the Dimrill Dale. Is there anything a hobbit should

know about arriving at the shining portals of the

Dwerrowdelf?'

'Nothing. The way

is wide and well-marked and we have no gates. We do not fear

attack, being all but impregnable anyway. And a single hobbit on

horseback is not likely to cause much alarm. Even the great

western gates of stone that have been rehung and given new

passwords are rarely closed, save at night. Mr. Fairbairn only

need state his errand to the gatekeeper and he will be led along

the proper passages and taken good care of. Such a visitor usually

would find an audience with the King extremely difficult, if not

impossible. But the names of Radagast and Cirdan should gain you a

few moments, if I am not mistaken. Messengers are treated with due

respect, and the dwarves have not forgotten the proper forms. You

should address King Mithi as "Lord," Mr. Fairbairn.

Other than that, if you are polite you can do little, being a

stranger, that would give insult.'

Radagast and Tomilo took

their leave of the dwarves early the next morning. A heavy fog had

settled in the river valley overnight and Drabdrab was dripping

with dew as Tomilo slipped up into his saddle. Pelling snorted and

blew great draughts of smoke into the heavy air, trying to warm

his nostrils for the long day ahead. Radagast checked the horse's

hooves carefully and rubbed his ears, speaking softly to him. Then

he wiped the mist from his own saddle with his brown cloak before

mounting. The dwarves were pulling on their great packs as

Radagast and Tomilo rode past.

'My good dwarves, you said you were travelling to the Blue

Mountains? Are you crossing the Lhun?'

'Indeed,' answered Frain. 'The old mines are all in the southern

range, of course. But our new mines in the northern range of the

Ered Luin have become most profitable. The caves we seek, and the

home of Kim, are some two days journey past the river Lhun, high

in the eastern slopes.'

'I

wonder if you would be so good as to give a message to the elves

as you pass the Havens, if it is not too much out of your way. I

know you have little love for the elves (except at times some of

the Noldor—since Aule rules the hearts of all of you), but if

you could let Cirdan know that I found someone to go to Moria, and

that I myself am gone to Gondor, it would be a great help to me.

It is a simple message and may be passed on by mouth to any elf

you meet.'

'We will if we can.

But won't you tell us what message goes to Moria and Gondor? If it

concerns the dwarves of Moria, it will concern us. And we had

rather not wait for the message to travel on the road we have just

covered and back.'

'I'm afraid

that is impossible, unfortunately. It is a message from Cirdan to

Lord Mithi himself. What he may choose to do with that

information, I know not. He may proclaim it as news of general

interest. He may not. But I suspect you will hear of it soon

enough, one way or another. I fear I have been imprudent in

handling the whole affair, and I apologize. I have grown

accustomed to talking freely in these untroubled times, and I am

afraid I have said too much. I should have said nothing at all,

and saved you from needless concern. But again, thank you for your

news of the east, and give my message if you can. If you cannot it

is of little importance.'

Radagast and Tomilo left the dwarves and rode over the bridge,

passing into the open lands beyond. The day was warming quickly,

and the two riders hoped to leave many leagues behind them by the

end of it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

![]()

![]() Chapter

2

Chapter

2![]()

An

Accumulation

of Mysteries

Despite the

prosperity of the Fourth Age, the wide lands between the Baranduin

and the Greyflood remained mostly unpopulated. It was almost fifty

leagues to Tharbad, and from the bridge at Sarn Ford to the new

bridge at Tharbad there was little to see. The ground was rocky

and flat, with few trees and little vegetation of any kind. At one

time, the Old Forest had covered much of Cardolan, reaching even

to the northern parts of Enedwaith. But the cataclysms at the end

of the First Age had temporarily inundated a large part of Middle

Earth, from Beleriand all the way to the Hithaeglir. Beleriand

remained drowned to this day, and Ossiriand as well—save the

small regions of Forlindon and Harlindon. The Gulf of Lhun had

taken Mount Dolmed and the cities of Belegost and Nogrod, and many

other fair things had passed away forever. The receding waters

left Eriador changed but intact. Most of the Old Forest had been

swept away, never to return. Cardolan arose from the waters a

desolate place, and it had remained desolate in many regions to

the present age. As Tomilo looked north toward the South Downs and

the Barrow-downs, he saw nothing but low bushes and dry grass as

far as the eye could see. Brakes of hazel and clumps of thorn

there were, and dry rivulets meandering through the rough country

like a weird sunk-fence dug by a madman. To the south it was much

the same—a few stands of trees here and there in the distance,

and some old willows and oaks along the line of the Brandywine as

it snaked its way to the sea.

The two travellers had been riding all day through this empty

heath, stopping only to eat and to water the horses. Radagast had

been grumbling to himself since the bridge at Sarn Ford; and

suddenly, in the late afternoon, he spoke up, startling the hobbit

out of his musings on the landscape.

'I have made a terrible mess of the whole affair already,' he

began, almost to himself, or to Pelling. He stroked his beard and

fumbled with the brown stone about his neck. 'I either say too

much or too little. For ages I have spoken to almost no one but

the birds and beasts, and now I am expected to converse with

dwarves and hobbits and who knows what else. I am not fit for it.

I am the wrong one to trust with such things. That meeting with

the dwarves was a complete disaster. Imagine, sending dwarves with

messages to elves, and hobbits with messages to dwarves! I don't

know what I am thinking. But I can't do it all myself. It is too

big for me, I tell you.'

'What

is too big?' asked Tomilo, somewhat surprised to see a wizard out

of sorts.

'This. . . this whole.

. . Oh, I can't say. That's the problem. I wish Gandalf hadn't

gone back, sailing away just when things look really bad. Bother,

I shouldn't have said that either. See, I can't be discreet, as

wisdom demands. I was always the least of the wizards, and now I'm

made to feel it. I'm surprised Cirdan even trusted me as the

messenger. Gandalf would never have told a band of travelling

dwarves of the existence of a message to their king. It is absurd.

I am a counsellor, sent here to gather information, not pass it on

like a fool at any chance meeting.'

'I don't think you did any harm. If we have all become too

trusting, it is only to be expected. Times are good.'

'For the

present. Good

times cannot last, my dear Mr. Fairbairn, and being overtrusty is

not a custom that ever lasts, for it undermines itself. I must not

let my tongue wag, and I must think out my policy

beforehand.'

'Well, your hints

are as disquieting as any news could well be. I won't ask you

about the message, since I can see you feel you have said too much

already, and since I will likely find out soon enough, when I am

in Moria. But I wonder if you, or Cirdan, have had the foresight

to send messages to the Shire? I am sure the Thain would be

interested to hear of any news that concerns the rest of the

world. And he might take it ill hearing the news secondhand, from

the king's messengers, or from my report to Farbanks.'

'Don't worry about that, my friend. The Thain has likely already

been told, since your lands border on the Western Sea. The Tower

Hills are only a short ride from the Havens. On this, the hobbits

will be the first to know rather than the last. Cirdan remembers

Frodo Baggins and his companions, and the Shire will never be left

out of the reckoning of the wise again.'

'That is well, at least. Still, whatever concerns you had about

our talk with the dwarves cannot come to anything, surely. The

dwarves of Moria mean no one any harm, do they? I don't see how

what they know could be of use to anyone, even the enemy. And

there is no enemy. '

'Doubtless

you are right. There is no enemy, for the present. Besides, it is

not that I am worried about leaking any information. I only told

them of a message they will hear of later, in the proper way. But

that is what I mean. It was not proper. They should have been told

or not told. I must relearn the proper forms. I must become more

wary. I must learn to speak to strangers as one of the wise would.

I must not say more than is necessary, or show weakness. There may

come a time when such traits might be fatal.'

'Oh my! I hope not, or we shall all be dead, and me first of all.

Surely it is not as bad as all that!'

'I have already said too much.'

'Well, then, let's change the subject, by all means. Evening is

coming on, and I can't be imagining such things. Let's see, why

don't you tell me what these letters on my saddle mean? It will be

dark soon and you won't be able to see them at all.'

'Yes, you are right. I think we have had enough riding for today.

I am in a great hurry, but I think there is no need for us to

travel after dark. When I leave you at Tharbad, I can make

whatever speed I want. For now, let us be easy with poor Drabdrab.

He is not used to these distances like Pelling.'

Soon they dismounted and unpacked the horses. Once camp had been

made and a small fire was going in preparation for the night,

Radagast approached Drabdrab and studied the saddle closely for

many minutes.

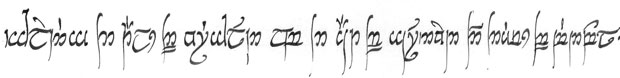

'Well, Bombadil

must have had this saddle a very long time, though how he kept it

in this condition it is beyond my skill to tell. I know something

of the tanning of hides and of the preservation of things, but I

myself could not conjure a spell to make leather last this long.

This saddle comes from Hollin, the very place you are now headed.

It was made sometime in the Second Age, before its destruction,

and long before the destruction of Numenor. It bears the

inscription of its maker here, you see?—it says in Quenya, the

language of the Noldor, Galabor

of Hollin made this.

Written quite prominently. And here below, writ even larger,

running in this great arc, the letters say, Arethule,

child of the West, Varda protect thee.*

And see all the fine tracery. These are symbols of the Noldor. The

two trees and the stars. Above Galabor's name are the phases of

the moon, punched into the leather. And these are the

Silmarils—see, below the central star—that the First House of

the Noldor still used as signs even after the defeat of Morgoth

and the final loss of those gems.

'This

saddle was made for a child—a very special child, I should

say—for most leatherwork at that time would have been inscribed

in Sindarin rather than in Quenya. Saddlework was mostly a thing

considered too vulgar for such high speech. This elfchild,

Arethule (which means "sun spirit"), was no doubt one of

the children of the contingent of High Elves living in Hollin at

that time. Celebrimbor, grandson of Feanor (who invented this

writing), was one such. His inscription was on the west doors of

Moria before they were broken. I think the dwarves keep the

fragments of that door as heirlooms in the vaults of Khazad-dum.

The parents of this child may have been of the same family as

Celebrimbor. If Galadriel were still in Middle Earth, she might be

able to tell us somewhat of this Arethule. She was of the Third

House of Finwe and Celebrimbor was of the First, but she and

Celeborn spent many years in Hollin in the Second Age, I believe,

before going on to Lothlorien. No one else but Bombadil could say

aught of such a thing as this saddle, I think. Keep it well,

Tomilo, while it is in your care! It is a thing of great worth,

and would be greatly treasured by some in Imladris or Lorien, were

it known to exist. I wonder how it came into the hands of Bombadil

in the Old Forest? It is a question for our next meeting. Come,

let us tend the fire and prepare our dinner. The light is now

gone.'

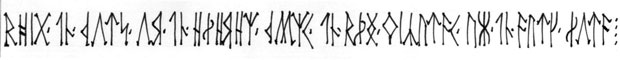

*Here is

a letter-for-letter translation: galabor

eregioneva essent/ arethule/ tartanno numenello fanuilos le tirai.

You will notice that two different r's

are used. The r

in Galabor is a final r,

and so is the only one that is not long. The e

in essent

is not written, since it

would be understood that no word begins with ss.

Also, 'to make' is a very common verb: it had become unnecessary

to differentiate it from words beginning iss-

or oss-,

&c. Proper names beginning with a vowel still required an

initial character, however. That is why Arethule does not begin

with the Quenya character for r.

Since the tehtar

(the super-character devices)

indicated a following vowel in Quenya, but never a preceding one,

the initial A

must be indicated with the

character used. The 'a' tehtar was often also used, especially as

a decorative flourish in formal writing. This was not read Aa.

In this mode used by Galabor the Quenya y

character is a long r,

the y

with a doubled tail is rd,

and a tripled tail is rt.

The Quenya character u

translates nn.

Tirai is

subjunctive.

The

next morning Tomilo and Radagast set out once more. Tomilo was

amazed to think that he was sitting on an heirloom of the High

Elves, made in Hollin in the Second Age. As they galloped through

the empty lands, he became lost in his own imaginings, taking him

back in time—a time when wondrous creatures still walked in

Middle Earth, passing with grandeur and terror. Elves with

glittering swords and rings of fell power, tall men with high

helms and burnished shields, great worms and foul goblins and

Witchkings in black robes.

It was true, the King in Gondor

was yet a person of great majesty and lineage—or so Tomilo had

been told, for he had never seen him. And elves still lived in

faraway places, in towers by the sea or in great caves in the

forest or in tall trees on the other side of the mountains. But he

had never seen them either. Even when he had lived in Westmarch,

only a few leagues from the Havens, he had not encountered a

single elf. There were tales of them, to be sure, and reported

sightings. A messenger even rode through occasionally on the main

road for all to see, or so it was said. All the same, Tomilo had

not seen one. He had never even seen a dwarf until two days ago.

All borders were supposed to be open, after the fall of Mordor and

the rebuilding of Arnor. And yet little had changed. In good

times, folks kept to themselves. They kept their thoughts to

themselves, and took care of their own.

Men had passed through the Northfarthing quite often, soldiers of

Arnor and the builders and settlers of Fornost, reclaiming all the

fertile valley between the Hills of Evendim and the North Downs.

But even these, after a quick look at the settlements of the

hobbits, and maybe a stop in the taverns for a taste of 'halfling

beer', had returned to their own towns and farms, and were mostly

never heard from again. Except for pipeweed, and the occasional

trade of a pony, the products of the Shire did not interest the

men of Fornost. They already had their own markets in the south.

And the tastes of men and hobbits, whether in food or clothing or

housing, had little overlap. Each community was content to keep to

itself. No mixed town, of the Bree sort, had formed during the

expansion of the Shire and the emigration of men from Gondor to

the north countries. It was once thought that there might be, and

King Eldarion, son of King Elessar, had promoted the mingling of

man and hobbit, or at least the sharing of economies. He had

reversed the decree of his father that had forbidden men to enter

the Shire, and had encouraged friendly relations between the two

peoples. Men were still forbidden to settle in the Shire, but they

were not forbidden peaceful excursions, or the building of

relationships, business or otherwise. And hobbits were encouraged

to settle in Arnor in any way they liked—in the towns or out of

them. But it had never come to pass. There was simply too much

resistance from within. The hobbits of the Shire were proud of

their independence and the men from Gondor were also content with

their own society.

Two more uneventful days passed on the

road. The riders met no one and saw no other beast larger than a

squirrel. Radagast searched the skies for birds of good omen or

ill, but found neither. Near the end of the third day from the

ford, he and Tomilo weathered a short storm that blew in violently

from the southwest. They could see it coming for hours and took

shelter at last under a lonely tree; but though it poured hard

enough to sting any exposed skin (and threatened to spook the

ponies with the loud thunder—only the soft words of Radagast

kept them from rearing), it did not last. They returned to the

muddy shining road and continued their progress under the still

growling sky.

The next day was

dry. The storms had gone on over the Misty Mountains to soak the

uplands of Lorien and the Dimrill Dale. Tomilo and the Wizard had

fallen into their accustomed silence after breakfast, and the

hobbit had been daydreaming again—thinking of the times when

adventures actually happened.

In the books he had read of the old times, a hobbit couldn't so

much as leave his hole without terrible, dangerous, interesting

things happening. Tomilo didn't really want anything

too interesting to happen, but a little minor adventure might be

welcome. Meeting someone that Radagast could zap with his staff,

for instance. But Radagast wasn't a wizard like Gandalf, thought

Tomilo. Radagast didn't even carry his staff. There it was, just

tied to his saddle, sticking up in the air, useless.

Tomilo's thoughts were suddenly interrupted by Radagast himself.

They had been riding all day, with only short pauses to rest the

horses. Radagast had not spoken since midday.

'We are about five leagues from Tharbad. We will camp here and

make the crossing tomorrow. There are marshes we will have to

cross before we get there, and they will be better managed during

the day, when we can ride through them quickly. During the night

they would give the horses (and us) little rest, even this late in

the year. It is still many weeks until the first frost, except in

the mountains, and the flies in the marshes are yet a nuisance to

travellers on the road. Here the ground is firm, and there is even

a bit of dry wood for the fire. Come, let me tell you what to

expect tomorrow.'

Tomilo

followed Radagast off the road and into a loose thicket of

brambles and scrubby trees, gnarled and blasted as if by passing

flames. A white fungus covered the ground here and there, and the

roots of the little trees rippled the ground like waves,

threatening to make sleep very difficult. The earth appeared to

offer no flat spot large enough even for a hobbit to lie down upon

in comfort. Pelling and Drabdrab, meanwhile, entertained no such

fears. They would sleep standing. For now they rustled through the

undergrowth, searching for late shoots or the scent of anything

soft and green. Radagast wandered off in search of water. Tomilo

made the fire.

Over a frugal

meal of bread and sharp cheese and apple cider warmed over the

flames, Radagast gave Tomilo the directions for tomorrow. After

the bridge at Tharbad, Tomilo would be on his own. Radagast must

go south with all speed, and Tomilo must turn toward the

mountains. There was a road that followed the Glanduin for almost

forty leagues* before crossing it and turning north.

'You must take this road with good speed,' Radagast told the

hobbit. 'Drabdrab should make the journey to Moria in four days.

Five at the most. The crossing of the Glanduin is a ford, not a

bridge; but it is shallow and slow, save in the spring when the

snows melt. You should have no trouble with it now. For a few

weeks in May it is swift and treacherous, and for this reason it

is also called the Swanfleet. Swans do not frequent the upper

reaches of the Glanduin, near the mountains. But further down, in

the marshes at the confluence of Glanduin and Gwathlo, there are

great flocks of swans and geese and ducks unnumbered, especially

at this time of year. They stop over on their long flights from

the Bays of Forochel to their wintering homes in Umbar and Harad.

In a few weeks the waters of the Nin-in-Eilph, the Waterlands of

the Swans, will be white with the pausing flocks. You may also see

some from the northern vales of the Anduin, who fly over the Misty

Mountains to join their western cousins in the long flight south

over the White Mountains. These birds from the east pass over the

Misty Mountains just as we do—through the Redhorn Pass.

'Once you have crossed the Glanduin, simply follow the dwarf road

north and east some ten or twelve leagues until you reach the

Sirannon, the Gate Stream. This you follow to the gate, of course.

There were once some stairs and some falls as you made the final

approach to the Western Wall, but I don't know if they have

survived the rebuilding of the West Gates. But I expect you will

have been spotted by dwarves by this time, and will have an escort

the rest of the way.

'An escort?'

interrupted the hobbit. 'I'll be a prisoner, you mean.'

'No,

no. Don't be absurd, Mr. Fairbairn. None of that. No one keeps

prisoners in the Fourth Age. But don't be suprised that the

dwarves should want to keep an eye on you. It is their

kingdom, after all. They can't be expected to allow

strangers to wander about willy-nilly.'

'I

suppose not.'

'After you have

delivered the letter to King Mithi, and taken some refreshment and

rest, you will no doubt wish to return as quickly as possible to

your garden and your work. Stay as long as you like in Moria. I

don't mean to rush you. Mayhaps the great caves of the dwarves

will be of more interest to a hobbit than to a wizard—what with

your instinct for burrowing, I mean. At any rate, ride back the

way we came. There is no other way, unless you want to return

through Rivendell and take a month in the journey. When you arrive

in Farbanks, simply release Drabdrab at the north end of town, and

be sure he is well watered. He will make his way back to

Bombadil.'

The next morning they rode on. The flies of the

marshes were still torpid from the cool night air, and bothered

them little. Before long they came to a grey bridge, some nineteen

ells across, made of stone and marly earth. There were carven

figures at each entrance, smaller versions of the great pillars of

the Argonath, but much less foreboding. Rather than the helm and

crown of the ancient kings, these stone heads bore only the single

star of the House of Elendil. They were carven in the likeness of

Elessar, who had refortified Arnor and rebuilt much of the road to

Arthedain and Fornost. In the right hand of each figure was a

marble bough—an image of a shoot from the White Tree of Gondor,

scion of Nimloth. And the left hand was raised, not in warning,

but in greeting.

As Tomilo rode

between the figures and over the waters of Gwathlo he thought of

the King now in Gondor, great grandson of Elessar, the fourth of

his line. Tomilo had never considered that he was part of a larger

realm, that the Shire was only a kingdom within a kingdom,

suffered to exist only by the goodwill of a great man in a faraway

city of towers and flying banners and white trees. A great man

Tomilo would probably never meet. Tomilo paused at the middle of

the span, and Radagast turned also to peer at the slow-moving

waters.

'What is his name? I

mean, what is he called, the King in Gondor?' asked Tomilo.

'He is Telemorn, son of Celemorn, son of Baragorn, son of Aragorn.

But he is called King Elemmir, after the star Elemmire, one of the

first stars in the heavens wrought by Elbereth before the first

days. See, there it shines even now, the star-jewel, blazing high

on the breast of Menelmacar.'

Tomilo looked up, but he could see nothing in the bright sky but

blue beyond blue.

*The Numenorean

measure of distance was the 'lar,' equal to about three English

miles. I have followed Professor Tolkien's usage of the 'league'

to translate 'lar,' making the forty leagues in question

approximately 120 miles.

'Yes, the

stars are there, even during the day, my good Mr. Fairbairn,'

laughed Radagast. 'They do not run away and then scamper back,

just for your delight. But the sun drowns out their dim glow from

the eyes of most.' The wizard stared at the sky intently and

seemed to lose himself for a moment. 'Hmm, where was I? Oh,

yes. King Elemmir has ruled only a score of years, following his

father King Eldamir who ruled almost a hundred. The new king is a

young man, by the measure of the Numenoreans, being not yet

seventy, I believe. I have seen him only once, when he was a boy,

in the Druadan Forest. He was beating a small drum, trying to call

out the Druedain, the Woses. But the little men would not show

themselves, not even to a future king of Gondor. I remember

Telemorn complained, and said, "They might at least beat

their drums in answer." But it was to no avail. He and his

escort had to return to Minas Mallor with no new stories of the

Pukel-men.'

'Pukel-men? Woses?

Who are they? Are they dwarves?'

'No, no. They were not fashioned by Aule. They are one of the

strange creations of Iluvatar. Although of much the same stature

as dwarves, they are far more nimble. Also, they love to laugh,

when they are with others of their own kind. They do not delve and

have no love for wealth or hoards. Dwarves do not like woods, but

the Druedain will live nowhere else. There are few left in Middle

Earth, and it may be that the loss of woods and the loss of the

Druedain are not unrelated.'

'Do

you think there are Woses in the Old Forest?'

'Not now, at any rate. Before the flood, when the Old Forest

spanned much of Eriador, I should think that the Druedain

flourished there. But now, none are left. The only two-legged

creatures in the Old Forest are Bombadil and Goldberry. And

perhaps one other.'

'One

other?'

'There I go, getting

ahead of myself again. There may be one other that you might

include. But he is not a man or elf or halfling or dwarf or wizard

or sprite. And he prefers to keep his existence to himself—much

like Bombadil and Goldberry. The Red Book

has been a source of some frustration for them, if

you must know, for they do not want visitors. The scouring of the

barrows has left them open to nosy neighbours from the east, and

they have been forced to live further down the Withywindle. This.

. . this two-legged creature also wants to be left alone, so

please forget I said anything. Besides, he is no one to go

visiting. His welcome is unlikely to be warm.'

'Well, the mysteries of the world do

accumulate, travelling with a wizard. Especially one

with a loose tongue. But back to the King. Is this King

Elemmir the one you must deliver the message to now?'

'Yes. Precisely. And if I don't train my tongue in the next

fortnight, it could be very unpleasant for me. Telemorn is said to

have a reputation for irascibility. And he is not likely to be

impressed by a wizard, a brown one least of all. A messenger with

bad news is never wanted. An unexpected one, even less. An

unexpected one with a stained cloak and overworn boots—well, he

is in some danger of being thrown into the Anduin.'

'Surely you exaggerate! Are you suggesting that I may be in some

danger in Moria? Are the dwarves likely to be inhospitable, on

account of this message?'

'No,

you are right. I am getting overexcited about this whole business.

You have nothing to fear, my dear hobbit. But do be prepared for a

few awkward moments. Especially on the day after you first meet

with King Mithi. Once he reads the message, the air in the caves

may be a bit thick for a while. I can tell you this much: there is

nothing urgent about the message—there will be no muster, no

general upheaval. You will not be caught in any call to arms or

flight to the strongholds or any such thing. But the King and his

counsellors are likely to be a bit tense. They may question you.

They may be angry that you can tell them nothing more. Or that you

are a hobbit. But I do not think it will go much beyond that.

Remind them that you are under the protection of Cirdan, the elves

of the Havens, and myself, as well as the Thain. Offer to return

with messages, if you can think of nothing else. You need not

return past Farbanks: I will have riders going west before winter,

and I will instruct them to ask in Farbanks for any letters to be

sent on to Cirdan.'

'If I can

think of nothing else? You make it sound like I will be lucky to

get out at all! I have more than half a mind to turn around

and ride back now. You never told me there was any danger!'

'Not danger, Mr. Fairbanks. Never that. Let us say,

unpleasantness. Some small unpleasantness. You know how dwarves

can be. Testy. No more than that. Now please don't get in a huff.

They will have no reason to keep you there, no matter how they

feel about the news. They really have no use for hobbits, and

dwarves don't keep slaves. No matter what else may be said about

them, they are not that.'

'All

right, enough. Please don't say another word about slaves.

Everytime you try to relieve my fears, you end up adding to them.

I will go, Mr. Radagast. But I consider you deeply in my debt. And

I don't believe I will know how deeply until this is all over

with.'

Radagast and Tomilo passed the bridge and rode down

to the crossings beyond. About a league from the river the road

diverged. To the left it ran directly toward the Misty Mountains

hanging ominously in the distance. To the right it curved in a

long arc, disappearing amongst the trees and boulders. Somewhere

beyond it straightened out and ran almost due south into Dunland.

This was the New South Road, identical to the Old South Road but

for its improved crossings and general upkeep. Bridges had

replaced fords, and here and there a small village had taken root

where the road crossed water or skirted a wood. There was even an

inn in one of these villages, near the halfway point from Tharbad

to the Gap. The inn was run by men of Gondor, not by the

Dunlendings: indeed the entire village consisted of settlers from

Gondor. The only exceptions were the groomsmen who worked in the

stables. They, of course, were of the Rohirrim. The villages of

the native Dunlendings were mainly off the road, and these

villages contained no inns or taverns. Even after three centuries,

they neither travelled nor wanted guests or other company. Much

like the Woses, they only wanted to be left alone.

Tomilo

looked at the mountains in the distance. They were still small and

indeed misty. They looked much like a line of low clouds, and one

had to squint to make out where the clouds of mist stopped and the

mountains of mist began. Suddenly Tomilo heard a distant honking,

high above and to the left. He looked up and watched as a great

vee of white birds wheeled over and turned to the south. He

listened to the fading honks until they were out of sight.

He turned to Radagast. 'It makes me want to go now and see the

swans where they gather—what did you call it?'

'The Nin-in-Eilph?'

'Yes. Just

that. I should think they would be easier to meet than the

dwarves.'

'Now, now. Don't get

yourself all in a pother. I tell you the dwarves are more bark

than bite. And, as beautiful as the swans are in the marshes, I

must tell you that Khazad-dum is also something to see. You should

be pulling at your toes in anticipation, not grinding your hobbit

teeth. Even an avoider of palaces, as I am, would make a week's

journey to see the Dwerrowdelf for the first time, and count it

time well spent, even with no other business to be done. See, look

at Drabdrab. He knows where he is going. Hollin never forgets the

elves, and never loses its mystery, no matter how many ages come

and go.'

Tomilo felt the pony quivering under him, and

fancied that the beast did indeed seem to want to gallop off down

the road. This put him somewhat at ease. Also, he thought how he

was on a saddle that might be quivering in anticipation as well.

This seemed somehow absurd, but also somehow fitting, and the

hobbit smiled to think he had thought it.

'I hope everything goes well in Gondor, with the King and all. I

guess maybe I won't see you again. In a while, I mean,' stammered

Tomilo.

'Yes, this is good-bye

for now. I am sure I will find something to say when I get there.

Let us hope it is not too awkward. Well, I must learn to speak

sometime. And this is the time, by all appearances. Be that as it

may, we may meet again, my dear hobbit. I must say that Gandalf

was right about the halflings, as he was about everything else:

your reticence and honesty both play well, even in the ears of the

"wise"; and, for myself, I have no fears about your

ability to deliver the message to the dwarves. And I shouldn't be

surprised to see you again. Eriador is not so far out of my

reckoning as it once was. Stay on the road, and don't stay too

long in Moria. Winter is not far away, remember! Farewell!' With

that he turned Pelling and galloped down the right hand way, his

brown cloak flying out behind him and waving above the dust.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

![]()

![]() Chapter

3

Chapter

3![]()

An

Unexpected Welcome

Despite

Radagast's final words of encouragement and Drabdrab's apparent

excitement, Tomilo still felt a bit glum as he made his way along

the Glanduin road. The unknown contents of the message weighed on

his mind, as did all the veiled forebodings of Radagast. The

letter itself was in his pack, safe and sound. He reached back to

be sure the pack had not come loose, or fallen off. It was still

there, all right, but touching the leather only made him think of

the letter all the more. When Radagast had given it to him as they

parted, Tomilo had only glanced at it for a moment (he did not

want to seem too curious). But he did see that it was sealed with

wax that bore the impression of the brown stone that hung about

Radagast's neck. Tomilo assumed Cirdan's seal was inside.

Tomilo wondered what a letter could say that would make even a

wizard turn into a fool, second-guessing himself and forgetting

simple things like watering the pony. The hobbit was clever with

his fingers and he thought he could probably get the letter open

without damaging the wax. No, that would be absurd. Preposterous.

It was even more repugnant to the hobbit than the idea of living

in ignorance. Normally he would never even consider opening a

letter not addressed to him, but this situation had put him out of

sorts. This surprised him almost as much as anything: that he