|

|

return to 2004

A Report from London

by Miles Mathis

As an artist and a bit of a Luddite I don't

normally keep up with the various media. The trash created, both physical and

psychical, cannot be fully composted, and my mind wanders in greener

pastures. I take no newspapers or magazines, never watch TV news, and rarely

browse news online. Occasionally I seek specific information on current

events, but I have found that most of my research time is better spent reading

old books. My friends and relatives send me clippings as grist for my

columns; left to myself I fear I would never be au courant. I store

and assimilate all that meets my eye, but seeking out the bad news of the

present seems to me somehow morbid. I face it only because I must—I flee but

it always finds me.

Here in Europe it has found me all the quicker.

In seeking new friends and clients, I run more slowly from society, and the

media leaps upon me in its stead. This farce has its better moments, one of them

being now, when I can report to you the latest art news from London. This may

be of interest to American readers especially, who find it difficult to get

non-war, non-business news from the rest of the world.

As it happens, it is a very eventful time for art in Europe. In this article

I will only report on London, since much of my news comes from the BBC. But

throughout Europe changes that parallel those in London are taking place, and

realism is advancing universally, I think I may say. Before you begin

cheering I must make clear what sort of realism is advancing. The big event

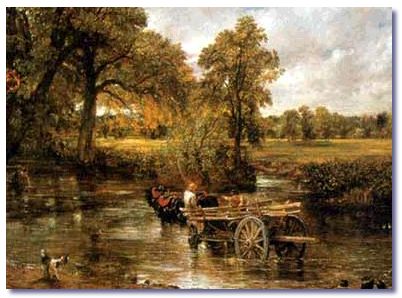

this week was the televised unveiling of a huge mosaic copy of Constable's The

Haywain on Trafalgar Square. Various English cities supplied the 144

tesserae of the mosaic, each one being shipped in at the last moment via

police escort. Film crews in helicopters followed the progress of the convoys

as the clock ticked suspensefully. At last the hundred-foot curtain fell and

the mob went wild, stunned by the sights and sounds extravaganza—and cued by

the monitors.

This circus was the idea of Rolf Harris, the host of a shockingly successful

series on art that has run since 2001. Rolf has been called the Bob Ross of

Britain (and if he hasn't, let me be the first). He paints in a sad, stilted

impressionistic style that beats Ross and Thomas Kinkaid only in that Rolf

can paint figures. A friendly, handsome, silver-haired man with a beard, Rolf

relies more on his unassuming charm and everyman demeanor than on any real

talent. He surrounds himself with famous amateurs and celebrities past their

prime—Jane Seymour was the eye candy at the Haywain debacle. But Rolf is

undeniably big business. Much bigger than Bob Ross and now arguably bigger

than Kinkaid. Kinkaid likely still sells more works (if retouched posters are

works), but Rolf recently had a show at the National Gallery. That would be

like Kinkaid having a show at the Metropolitan. [Such a show may be in the

near future: if the Met can show motorcylces and haute couture, a

Kinkaid show may be just down the pipe.] In addition, Rolf was just chosen as

The World's Greatest Artist in a British poll, beating out Damien Hirst,

Tracey Emin, and the other darlings of Saatchi Gallery and the Tate Modern.

What all this means for the future of art is

difficult to say. I think it would be naive to assume that it is an

unambiguously good sign. It is certainly refreshing to see such a huge crowd

turn out to witness and take part in copies from the old masters. But huge

crowds have also recently turned out for the Tate Modern: people in London

are bored—they will turn out for anything. You could unveil a hundred-foot

pile of wet nappies on Trafalgar Square and a million people would turn out

to see them stacked by celebrities and filmed from helicopters. In fact, the

art at the Tate Modern is the equivalent of wet nappies, and records have

been broken even without Jane Seymour and Cliff Richard on hand to leaven the

lump.

I have said elsewhere that the public is a

potential ally of realism, but an uninformed or misinformed public is only

another, and more powerful, enemy. I am reminded once again of Whistler's Ten

O’clock Lecture, where he said, in 1885,

Art

is upon the town!—to be chucked under the chin by the passing gallant—to be

enticed within the gates of the householder—to be coaxed into company as a

proof of culture and refinement... Alas, ladies and gentlemen, Art has been

maligned. She has nought in common with such practices. She is a goddess of

dainty thoughts... selfishly occupied with her own perfection only.

A public that thinks that art is the equivalent

of a quilting bee or a telethon or a State Fair is not much use to the

artist. I may not be an expert on the mass media but I know from experience

that any event that relies on the drawing power of celebrities—celebrities

from other fields, no less—is not an event to be trusted. And I know that any

field in which mediocre people are more famous than talented people is a

debased field, one that has been sold to some principle foreign to it.

In this case that principle is clearly economic. Rolf Harris and his sundry

allies and comrades have seen a way to put themselves in the spotlight and

make more money despite the fact that they have done nothing to deserve

either. In this they are absolutely on a par with the avant garde. In both

instances we see prodigious promotion and nothing to promote.

Some may argue that increased public awareness

and involvement is always a good thing, and that such involvement is bound to

benefit the realist movement as a whole. As much as I would like to believe

that, I don't. The type of awareness and involvement is crucial, and 100-foot

copies of the Haywain on Trafalgar Square cannot add to the public's

appreciation of the subtleties and depths of real art. Art as the

Bowdlerizing of another's work, art as a garish spectacle, art as a public

project, art as a media event, art as the gigantic, the equal-opportunity,

the therapeutic—all these misapplications and mis-definitions of art move the

public in the wrong direction. Replacing the mediocre political posing of the

avant garde with the amateur daubings of celebrities is not progress. It is

trading one shallow polluted pool for another.

As it turns out, both shallow pools are doing quite well, and there is really

no talk of replacement. London is truly Pluralistic, and Rolf and the avant

garde are co-existing in relative peace. Just today I saw Tracey Emin (famous

for putting her bed in a museum) on Room 101, talking at great length about

vomiting in cabs, her fame seemingly untouched by the growing regard for

Rolf. Also of interest: it costs nine pounds ($17) to get into the

avant-garde Saatchi Gallery, and yet they find no lack of visitors, though

the great British Museums are all free of charge now. It appears that the

public is beyond making judgments and drawing distinctions, and this is

hardly surprising since both the avant garde and the new realists have taught

them not to. It would be undemocratic, you see. So the public is now in a

position to applaud anything that is presented to them with the proper

fanfare. It is obvious how convenient this must be for the Mayor of London

and the Chamber of Commerce. In fact, it is convenient for just about

everyone except the truly distinguished and exceptional artists. They are

lost in the blast of trumpets, the tramp of feet, and the buzz of

helicopters.

Given all that, I still believe that the public could be enfranchised in the

rebirth of art. The solution, however, is not indiscriminate

involvement—luring them out of the house with bread, circuses and Jane

Seymour. That only encourages frivolity and the further degradation of all

serious enterprise and achievement. The government-owned media could be used

to give air-time and face-time to the finest artists, instead of to the most

ambitious mediocrities. If the same amount of time and money were spent

promoting truly fine art as is spent popularizing and glorifying make-work

projects and glitzy charades, art history would surely benefit. If the public

requires grand spectacles in open spaces, these could be arranged with

infinitely more taste and education. I am not suggesting we take their beer

and tarts from them, I am suggesting we treat the public as adults—as

emotionally mature people who may be capable of enjoying art as art, not as

car chase or fanfare or special effect. The 16th-century Florentines did not

need helicopters flying overhead and police-escorted convoys and

thousand-watt bulbs to appreciate the unveiling of the David. Surely

they were as ignorant as we are, and yet there was a tacit assumption that

even the most ill-educated and barbarous among them had a soul—and that some

corner of that soul, deeply buried perhaps, but hungry, might respond to art.

And if they didn't—if their souls were all maggot and vermin—they could go

elsewhere. It was not Michelangelo's job to appeal to every last wretch. It

was Michelangelo's job to create great art: it was the viewer's

responsibility to deserve it.

This all goes to say that we are doing the public no service in talking down

to it. In giving it what it wants or expects. Art does not have to be a

boring sermon or lecture, but it has to remain art. Beyond a certain point,

it cannot be vulgarized or popularized without losing its essence. A giant

copy of The Haywain is not art, it is an art event. The only possible

use of an art event is to educate, but, as I have shown, the event in

question mis-educated. Art is in great need of news coverage, promotion, and

public access. But not like this.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.

|